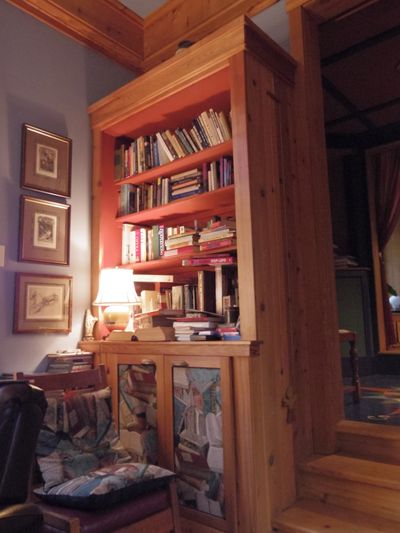

You're standing in the doorway to what Chris calls The Commons in A Pattern Language, but of course most people just call it the "living room." Here's what Tomo Furukawazono saw, standing on the top step to take this wide shot. We thank Furukawazonosan for sending us his images.

Now, as a guest here, you will ignore the mess. That's an order. If I took the time to tidy up before shutters clicked, I'd never get this memoir done. Here's what I can tell you about the room, tidy or not.

When the window openings for the room were being set, Chris stood looking into the forest (on the left of this photo) and said, “I’m seeing green for this room. Bottle green.”

As you can see, I wasn’t. (And his fee for doing interior design was an added $30K, which we didn’t have.) So it’s a blue room, five blues actually, all of them toward red in the spectrum and all of them wonderful with the warm cedar that’s everywhere in the room.

The walls inside the windowseat nook are a darker blue than the walls of the main room, the ceiling of the room lighter than its walls, the interiors of the waist-high bookcases that flank the fireplace the darkest blue of all.

The coloring of the room, and some of its design elements all grew out of a rug I'd had for years. Strangely enough, I'd seen it in a dream once, half a century ago, and then saw it rumpled in the corner of a friend’s garage. She was planning to throw it away and laughingly gave me “that old thing” when I asked to buy it. She’d admired a blue trench coat of mine so I brought that to her in thanks, new blue coat for old blue rug.

That rescued, raggedy rug is now the heart and center of the main room in this Timeless house. There’s something called Shabby Chic, which seems to value things that show wear. I think my love of long-used things goes back to appreciating sabi, the respect I saw for worn, repaired objects when I lived in Japan.

The rug ties the room together; the blues in the walls harmonize with it, the terra cotta of its flowers are echoed in the fireplace tiles and in the cinnabar of the bookcases; its squared-spiral border shows up in a tile band on the fireplace. The rug's pattern also has a definite center, and adds that to the space's sense of order—centers are key to Chris’s discernment of the order that underlies real beauty.

The drapes that can be pulled to enclose the windowseat are a batik from China Seas, and part of a Pacific Rim theme that developed as the house was furnished. JAG and I have both lived in Asia. My dad’s Navy career was mainly in the Pacific, including China, and I spent most of my growing-up on west coast Navy bases.

When Chris’s ever-aware right-hand guy, Gary Black, said something to him about how beautifully the colors in the batik picked up the gold of the room’s cedar, Chris almost heard him. Or perhaps he totally did, but it was hard for him to imagine or acknowledge beauty originating from anyone but him. His work had been one long battle against Philistines—how could anyone else possibly understand the right way to do these things? That mindset could extend to people who agreed with him—It seemed hard for him to take in the strange reality of being understood.

Throughout the house there are Chinese rugs. The chair cushions you see here are from China and Viet Nam. There's a large image of a China Clipper in the dining room, and mementos everywhere of our years of living in Japan and Viet Nam. Looking out the windows to the west, you can see ships of these times bound for Asia, and ships moving toward Seattle from distant Asian ports.

Many of the visitors to the house have discerned Japan in its form, and some of Chris's most important works were built in Japan so that influence here isn't surprising. (Others have thought the place looks English, and that's not surprising either.)

The main seating is four club chairs angled in an X faced in from the corners of the rug, with the fireplace between the chairs on the left. (Patterns 185 Sitting Circle and 181 The Fire) There's a pile of big floor cushions that guests younger than we are can throw around and sit wherever they like, including on the low hearth of the fireplace. And people sitting in the windowseat can either join the conversation or have their own. (Pattern 142 Sequence of Sitting Spaces)

As many as five people have hung out in the windowseat during parties, and it’s a heavenly spot to stretch out alone, for a nap. Both ends are piled with soft pillows, there are cozy throws to snuggle under, and a gnarled apple tree protects the windows from wind and rain. Several family members have recuperated from injuries and surgeries there. It’s a space that comforts and heals. (The Danes have a word for that: hygge.)

Chris writes that the chairs shouldn't match and there should be too many and people should be able to shove them around in new arrangements. That didn't work here. When this room had unmatched chairs, it just looked too busy, and really comfy chairs are heavy. The variety and mobility here come in the pillows and throws.

About throws. I think there's a reason for the name and that they shouldn't be folded. Folded says, Somebody took the time to neaten this and you better not mess it up. Thrown says, Come on in and grab this so you'll be cozy here. Hygge for sure and much more in keeping with Chris's sense of welcoming people into a space.

In his original thinking for this room, there were more windows, and more panes in the ones you'll see throughout this tour. Pattern 221 Natural Doors and Windows is a directive to make the size and shape of each window unique, perfect to its place in the structure. What do you see from there? How much light is coming in? Should the sill be high or low for its height in the building? (Pattern 222 Low Sill) How many panes should it have? (Pattern 239 Small Panes)

Windows are a very big deal in a Pattern Language building.

Each unique window was to be made by a superb craftsman, to Chris's specs. There were no ready-made windows that could possibly work. It would all be done within budget, according to Chris, but he didn't account for double-panes, an environmental requirement. He roundly objected, his only goal being beauty, not long-term reduced fuel use. So crew boss (and Chris's brother-in-law) Curt Brown set to work sketching out fewer windows and fewer panes in the ones that survived, so the windows didn't bust the budget. In a rare moment of acknowledgment, Chris looked at Curt's drawings and said they were exactly the changes he would have made himself.

Chris came to me when this space was barely framed, bringing the terrible, awful, you’re-going-to-be-upset news that there wouldn't be windows in the wall on each side of the windowseat.

I shrugged and said, Good. Room for pictures. As always, he seemed startled that I didn’t share his distress or argue with him about the importance of those two windows. When your whole artistic life has been dealing with opposition, a lack of it can be puzzling.

As you can see, this was something less than a catastrophe. The etching on the left, where there would have been a window if we were rich, is by British artist Brigid Marlin. It’s a depiction of Isis and Osiris. On the right is a beautiful encaustic image—"Balance Point" by Lynn Hayes.

OK, another end-of-the-world-disaster that wasn't at all: that large window in the windowseat? When the space was newly framed up, Chris stood there looking out and decided there couldn't be a window there at all. What? Well, the view was just awful. An ugly pile of rubble.

That was a case of a "given" that needn't be accepted. The pile had been created by a bulldozer and we just fixed it with the same machine. The land was smoothed out, and an apple tree planted. It's old and gnarly now, and has never produced an apple but is nevertheless quite beautiful.

Chris “did” the ceiling, something that rarely happens in contemporary buildings. It’s always just wallboard up there, right? But this ceiling is wood bordered with a heavy wood crown and crossed with a pattern of battens and medallions. Chris drew the size and shape of the medallions, the carpenters cut and placed them. Rusty Biggs, an ace among painters, sealed the amber-gold of the wood while painting the background the lightest blue in the room, without taping any of it and without getting a drop of blue on the wood. (He’d painted a lot of San Francisco Victorians.)

The Sistine ceiling it’s not. It’s simple and rough and strong, sheets of plywood helping stabilize the structure while visually holding the top of the room together as the encircling built-ins do embrace the bottom.

There’s light on three sides of this room, giving it wonderful shifting patterns as the sun moves from the high windows on the eastern, forest side, round to the almost-never-was windowseat window, then over to the west as the sun moves beyond the sea, to set behind the mountains. (Pattern 159 Light on Two Sides of Every Room) Two is a minimum to shape objects in the room with fewer shadows. Three goes beyond that into gorgeousness.

Way on the upper right, something ugly. Don't tell Chris, but we switched from baseboard heaters to heat pumps; the power bills were just too high and we needed to improve the air quality with the pumps' filtering function. This was the least-awful place to put a pump; the contractor of course wanted it above the windowseat alcove, which would indeed have been more efficient. So we went for beauty over efficiency, as Chris would have done.