BUILDING WITH CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER

This is a record, in a growing number of words and pictures, of the extraordinary years that Christopher Alexander spent bringing a Pattern Language house into being on Whidbey, a wooded island in the upper western corner of the continental US.

Alexander operates as a Master Builder — rather than handing drawings to a contractor, he was on site again and again, shaping the building himself, from sticks in the forest to a structure that seems to have always been there.

You're invited to explore and experience the process here, in the notes and photos I made of a time that shaped our lives as well as a profoundly beautiful house. You'll also see the results in THE TOUR, pictures of what's here now, with stories of how the spaces came to be.

I'm digging in boxes and drawers and computer files, scanning photos, transcribing hand-written notes...it will all be here as I get it ready and upload it.

Come back often. Send friends. This story needs to be known.

Starting with a Dark Hole in the Woods, Coming to...

Chris was on site for days when it was a small clearing in a forest. He came empty-handed, but with brilliant engineer Gary Black, and our Medlock-Graham family, all of us fetching sticks from the woods, driving to a hardware store for yellow tape, and pounding the shape of the house into the ground—with rocks and shovels.

In the posts below there are more photos—lots more—of how we got from sticks and strings to a Pattern Language house, the only one Chris did in the US Pacific Northwest.

Note that this website formatting cuts off narratives at odd places and insists on all photos being the same size. It makes things awkward but I'm not up for rebuilding it all elsewhere in less annoying form. Do click on the strangely disrupted texts, to see the rest of the words.

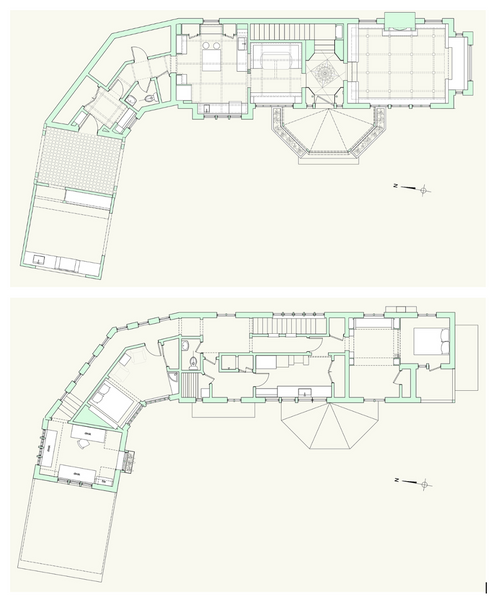

The Actual Floor Layouts

What got built, as the Master Builder process unfolded, onsite. There were formal "plans," probably done by Chris's students, exercises for them, sop for building permit grantors. Things changed a lot from the originals, things evolving as they had to, onsite.

moreIN MEMORIAM

Chris has died. He departed on March 17, 2022, from his beloved Sussex, gone but always present in his creations, his memory forever a blessing to all who come upon his works and feel their power, either in reading his words or by coming into a place he built, like this wondrous house, Dromnavarna. We are its stewards, holding it for those who need to experience the Quality Without A Name. When can you come? ...

moreCHRIS, CHARLES and THE MARY ROSE

A few years after we moved into the house we built with Christopher Alexander, a guy who had also been a client of Chris’s told us an interesting story.

He said that Prince Charles had asked Chris to design a museum to house the Mary Rose, an English warship Henry VIII had watched sink in 1545. It had been found under the mud of the Solent River and was being restored, an exciting moment in British history.

Chris and the team at his Center for Environmental Studies had set to work back in California and, when some ideas were ready, Chris flew to London to show them to Charles.

Arriving at the palace for the meeting, he was told that the Prince had left for Scotland, despite knowing Chris was on the way, that he was bringing plans, that he was expecting to meet in London.

It was December. It was snowing. And Chris had to make his way to Scotland to catch up with Charles.

Now this may seem mean, but we did laugh. John Graham and I had gone through five years of Chris’s own unannounced arrivals, departures and disappearances, seemingly unconcerned with how he might be inconveniencing us and the team working here. The guy telling us the story was laughing too, somewhat bitterly.

moreAlexander's Work

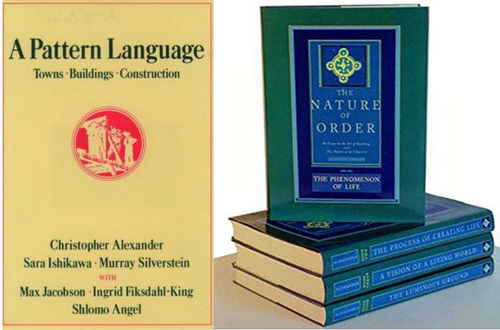

There won't be a primer here on Chris's work—there are plenty of other places for that; I've given you links to many of them—just click on More at the end of this post. If you already know his many books and projects, then jump right into this account of how the Whidbey House—or as I call the place, Dromnavarna, came to be. THE TOUR is a good place to start.

The image above is of just a few of his major books. Beastly expensive but available in libraries and highly recommended. He was a writer as well as a scientist and an architect.

Here's a wonderful bit of history—Chris debating Peter Eisenman at Harvard, in 1982. That's a transcript plus an analysis of the views of these two architects, the totally cerebral Eisenman, and Chris, who went beyond cerebral to understand the element of feeling in architecture, which he found lacking in the works of people like Eisenman.

To the profession and to those who study and write about architects, Eisenman was cool. His idea of creating deliberately disturbing buildings to match the awfulness of the world was popular among architects who, I think, see themselves as artists not architects. That's a problem.

moreJim Givens, Keeper of the Records

Jim teaches architecture at the University of Oregon and has been entwined with this place since coming here for lunch in the 90s, and taking what was long my favorite photo of the house.

In the fall of 2025, he was here for several days with his camera and a measuring tape. All the new photos are amazing, but I'll just put this new favorite here for now. No one had ever thought of turning on every light in the place. Brilliant—in every meaning of the word.

I hasten to add that this is not the huge guest lodge it appears to be. The building is one-room deep, two bedrooms and an office upstairs. Think of a double-decker train, skinny cars lined up. The largest room is 14 feet by 20.

I've shipped all Chris's original site- and floor-plans to Jim as the best custodian of all that paper. Not that I don't trust our heirs. But Jim gets this place at a profound level. I've told our kids that they should talk with him when they have questions or concerns about caretaking it all.

moreTHE LIST

A soft voice on the phone, telling me that he knows it's a terrible imposition but he's a student at the U of O (where Chris did a major project) and could he please come and see the architect's "masterpiece"?

Well, it's the only house he did in the Pacific Northwest but I wouldn't say it's his masterpiece.

But he did. On the list.

What list?

When Tomo Furukawazono came to the house—and took many of the photos you see here—he explained that Chris had made a list of some of his works and had ranked them, putting the visitors' center in Sussex at the top of those rankings, and this house just below it.

We'd never heard of such a list, but I started making inquiries and sure enough, it exists. I got the word from a network of people who have worked with Chris, one of whom—Michael Mehaffy—actually worked on The List, with him.

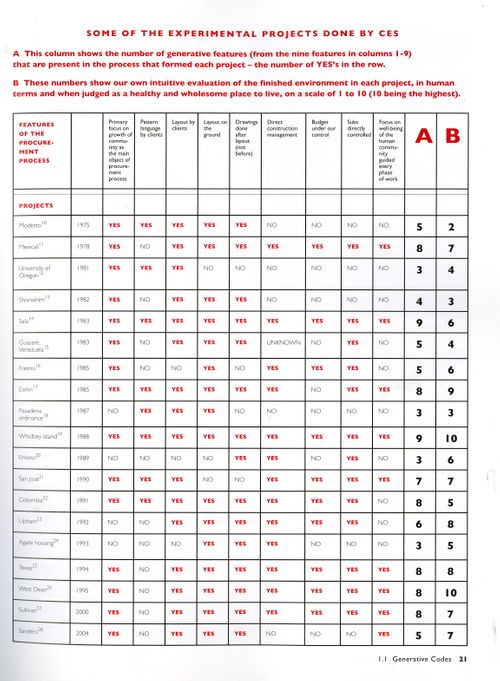

Found the book, New Urbanism and Beyond from Rizzoli, and you're looking at a scan of page 21, aka The List.

We just stared at it for a while, looking at a manifestation of Chris's mathematics-mindset charted with his emotional, intuitive search for the Quality Without A Name.

The List reminds me of the old crack about engineers trying to measure mud puddles with micrometers, but there it is. He scored the Whidbey House at 9 out of a possible 9 for the number of "generative patterns" he considers essential, and at 10 out of 10 in the B category of being "healthy and wholesome" for its users.

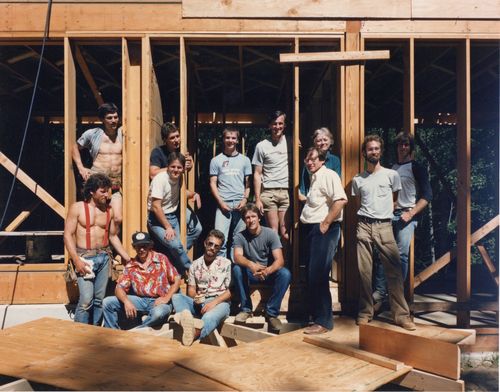

moreThe Team

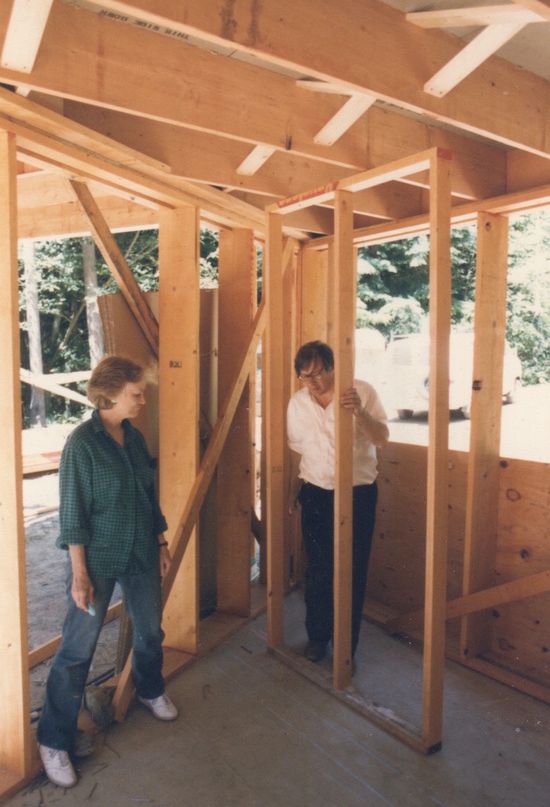

This is Team One, the first crew of CES/Dow, the company that Chris formed with contractor Jim Dow to do this one project.

It's a hot summer day in 1986. Team leader Kurt Brown, Chris's brother-in-law, is seated in the center, wearing a light patterned shirt. Jim Dow is behind him to the left, wearing a white T. Chris is, of course, the guy in black pants and a white shirt. I'm just behind him, and John Graham is to the left of me.

Other people followed over the years it took to finish, as the house grew and mutated. I wish all of them had signed their names in the foundation but alas, many names are lost. If you can put names to the faces you see here, and throughout this narrative, please email ann dot medlock at gmail dot com. I'd love to name them all.

For now I'll just say it was amazing how many architects, engineers, and urban planners put on carpenters' belts and became hands-on builders so they could watch Chris operate.

Jim Dow went on to build amazing projects all over the country, now employing hundreds of people in his company. He says, as I do, that seeing Chris in action influenced every thing he's done in the ensuing decades.

There are stories of how the CES/Dow was formed, and how it operated. Coming soon to this space.

moreSite Repair

There are hundreds of "patterns" in Chris's research into what makes a built space beautiful and comfortable, what makes it have the Quality Without a Name. Devotees of his work who have toured our place spot them and even call out their numbers in A Pattern Language.

Construction begins with a basic one: Pattern 104 Site Repair.

The topography of our land is best described as "rumpled carpet." There are 10 acres and almost none of it is flat, a place where you could make a garden or play bocce or sit at tables on the grass to have lunch.

The "repair" made for some tricky foundation-designing by Gary Black, Chris's right-hand man, an engineer as well as an architect whose motto is "A building built by only architects will fall down; a building built by only engineers will be torn down." One of Chris's best moves was involving Gary at every step of the process here. 33 years on, the house has neither fallen down nor been torn down.

The "face" of the house edges on the flat and the back is hung over the side of a rumple in that earthen carpet, preserving a precious flat area in front of the building, on the side that faces west, to the sea. You can see an edge of it on the left of this photo of the forms being placed for the great concrete pour.

moreThe Process

An architect is "supposed" to draw up some nice plans, hand them to a contractor, and go away. Unless said architect has absorbed Alexander's way of building. That architect is going to draw whatever plans the building inspector requires and then work day-to-day on the house, changing, adjusting, making it real in full form.

It's the ancient tradition of the Master Builder, the one who took the whole job from idea to reality. Not a great way to maximize the ROI on a degree in architecture, but the perfect way to make a structure that respects its placement and is shaped for it.

Chris talked at length about the surprises that develop day-by-day, even hour-by-hour, as a building takes form.

Great line from him about architects and their plans: "Architects get paid to pretend they know what's going to be there. But nobody knows until it's there."

Many more stories coming about working with Chris—five years' worth, actually.

moreThe Glitches

Did stuff go wrong? Oh hell yes, as in any and all human endeavors, especially when a lot of those humans are smart, creative, high-energy people.

This one was revelatory and confirming, and slap-your-forehead funny.

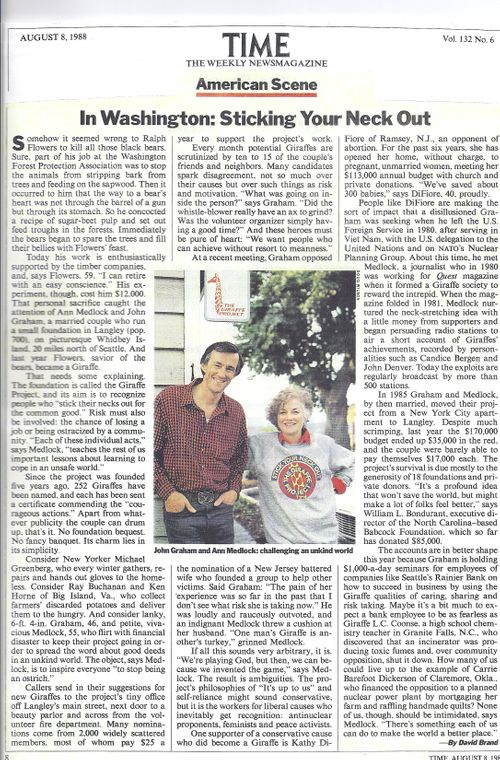

The article's dated 8/8/88, when we had been working with Chris for years. (We were then finishing the house while living in it, having run out of money before there were inner doors, second-floor flooring, or a real kitchen.)

Over the years, I'd read everything I could find by or about Chris, the better to work with him. And we suspected that we existed on his radar simply as The Clients, one needing spaces to be very high because he was 6'5", the other a bit of a pain because she had too many opinions about the house.

Chris was checking in every once in a while, tying up loose ends, and in one of his phone calls late that summer he said that he'd been in his dentist's waiting room and picked up a copy of TIME, opening it to this full page. There was astonishment in his voice. "What is it that you two do?"

He hadn't bothered to find out in all those years, and it sounded like he hadn't read the TIME article either. He just reacted to the photo and the prominence of the article.

moreTHE TOUR

You're at the door into the house, sheltered in a porte cochére formation we call the Gateway.

The Gateway is quite large and includes design elements Chris created for the Commons, deep inside the house. I gave one of the wood medallions from the Commons' ceiling to Steve Roache, the master of Aruba Tile Works on Vashon Island. Steve made multiple copies of it in rough, thick terra cotta taken from Mount Tahoma, a peak dear to the heart of JAG (John A. Graham, the mountaineer who lives here).

When Steve was turning them out, I thought they needed some detail, so I used a stick to cut a pattern of grooves into them. That "ornamentation"—plus leaving them unglazed—has helped the tiles acquire moss and show wear. (Pattern 248 Soft Tile and Brick) The tiles were first set in sand and only cemented in place in 2020. At this writing, we're still working on getting the grout darkened to the right smoky blue.

The lights above the door are massive, found after trying other lights that were just too puny for this structure—the house kinda laughed them off. Then I spotted...old freighter running-lights in a ship chandlery in Anacortes. Perfect. We just had to be sure they weren't visible from the busy shipping channel to the west. Don't want to cause any maritime disasters.

more