I learned a lot about the power of heroes from the world’s favorite teller of heroes’ tales, Joseph Campbell.

Back when I was getting the Giraffe Project started, friends and family were asking why I was putting so much into something that could well be a lost cause. Flying off to Paris from my Manhattan base to write a speech for the Aga Khan hadn’t been a bad way to make a living. Why was I going on and on with this Giraffe-stick-your-neck-out thing, these stories about real people being heroic? I wasn’t sure myself.

I got the answer on a trip west, after driving John Graham from San Francisco to Esalen, where he was giving his Politics That Heal seminar, a precursor to the workshops he would do once he’d joined me in the Giraffe Project. I had planned to drive back up the coast and work through the weekend. But I saw that Campbell was there, also doing a seminar. Having interviewed him for an article and taken his courses at the Church of the Open Eye and the New School in Manhattan, I knew I’d get more out of staying than going. I chucked my work plans and stayed on for two and a half days of Joe-on-Parsifal.

Campbell tracked the Parsifal story as a recurring theme in mythology, the story of the Holy Fool. This Fool is always considered a dummy by the smart, hip people who really know the score. There’s a mysterious blight on the land, nothing will grow and no one knows how to break the spell. The Holy Fool sets out to find the cause, right the wrong, save the people. He’s told he can’t do it, that he’s too dumb, too weak, too something, hearing from all quarters, “That’s not how we do things here," and “You just don’t understand." But he goes ahead anyway.

Parsifal would break the curse on the people by finding the Holy Grail. In seeking it he “went into the dark forest, alone, at a place where there was no path," the defining journey, Campbell opined, of heroism in European mythology.

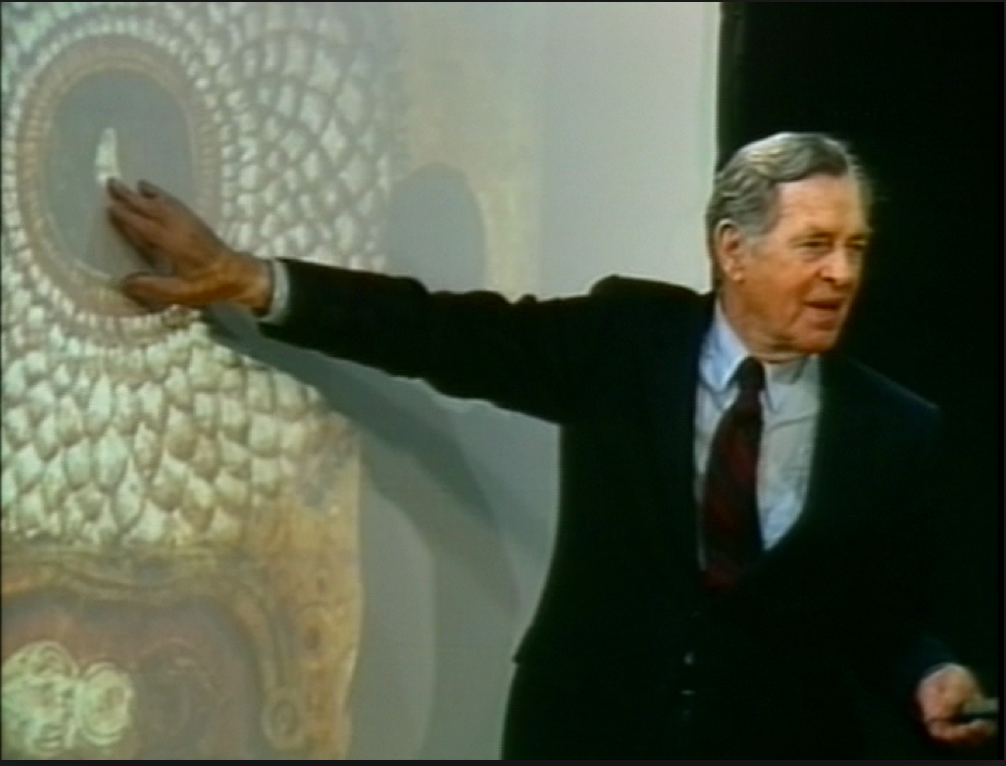

With sly humor, he told story after story of Holy Fools, and ended the weekend showing a slide of an ancient Tarot deck. Then he read a deck of modern playing cards as a spiritual journey through the suits, through the numbers and the face cards, to the Joker, descendant of the Tarot’s Fool.

The Fool is the most dangerous person on earth, Campbell explained, the most threatening to all hierarchical institutions, because he’s outside the suits, outside the numbers, beyond the powers of the royal cards. He has no wealth—see the hobo’s stick over his shoulder. He has no concern for naysayers—see the dogs nipping at his heels, and how he’s ignoring them. He’s about to walk over a cliff—see how unconcerned he is.

No one has power over this being. He’s not limited by his limitations, not listening to reason, not stoppable, not controllable. He knows what he has to do and he’s doing it, no matter what.

Campbell was—as he always was in person—brilliant, funny, irreverent, and charming. We talked with him before turning in at night, all of us watching the Big Sur surf crash onto the magnificent shoreline below our rooms. We delighted at meal times in watching him tweak the live-sprout eaters with his opinion that the perfect meal was a rare steak and a bottle of whiskey. “There’s a reason hard liquor is called ‘spirits,’ you know."

Driving back up the coast Sunday night, I had what now seems an obvious revelation—the reason I had been so obsessed with finding the heroes I called Giraffes and telling their stories was that these were our time’s Holy Fools; I had locked into an archetype that had me in thrall, one that was desperately needed in the spiritual blight of these times. No matter what it took, I would go on.

Back in New York, I talked with Campbell and told him what I was doing, what his seminar had made clear to me, how grateful I was that he’d shown me the reason for my obsession. I was amazed to see his eyes well up, and delighted to have his endorsement of my work, the work I’m still doing, a couple of decades down the road.