The reunions are always tearful, the regrets enormous. "Birth mothers" describe decades of worry and sorrow; their children, grown, newly found, say that not knowing who their birth parents were has been a gaping wound in their lives.

This isn't one of those stories.

I've seen them, read them, and realized, with both relief and a touch of puzzlement that although I’ve shared the experience, I haven't shared the pain. It may prevent regrets to be built, as I seem to be, without a rear-view mirror. My natural mode is to make the best choice I can at any given moment and to not focus on the choices behind me, wise or foolish. They can't be undone, but the next move can be chosen. What is it to be?

Getting pregnant when I was still a student was no doubt foolish, but giving my son for adoption was wise, the right choice for the time. I was in no position to raise an "illegitimate" child in '50s America and there were couples – well-established, older couples – who were desperate to raise children, ready and able to love and provide for those children, once they were legitimized by adoption.

Illegitimacy is a bizarre concept to me, a stunning manifestation of human hubris. An infant, wonder of wonders, arrives in the world and some construct of our prideful, rule-making culture declares this particular child less-than, extra-legal, flawed because his parents were not united by the civic and religious constructs we've invented.

Somewhere in even the most rule-bound heart, it must be clear that this is demented. Life given should be life welcomed. But that thinking was not the prevailing wisdom in 1954. The "right thing" had to be done, the family honor protected from fierce assault by society, my father's career in the Navy not jeopardized by scandal, and the child sheltered from the awful consequences of his unsanctioned birth.

My mother knew instinctively that the man-made rules made no sense, telling me after her first grandchild was on his way to placement in another household, "We should have kept the little guy, and the hell with the neighbors." In a more compassionate, less rigid world, yes, we surely should have.

But that was not the real world of the time. Girls "went away to school" in another city or went off to assist an aging relative for awhile, leaving before they were visibly pregnant, not returning until all evidence was gone and their babies were sealed off behind impenetrable barriers of laws and documents, never to be seen again.

Abortions were illegal but common, the time loss for the girl in question only a weekend, unless back-alley sepsis killed her. If you had enough money, there were costly, safe alternatives—"Oh we all went to Havana. There was a wonderful doctor there ..."

I took the long detour, leaving college, disappearing into a country house where an ancient, disapproving auntie hid me from the world as I grew condemnably gravid. When I had to make appearances at the obstetrician's office, I wore a wedding ring, used a false name. For the birth, I was a "Navy wife," her husband away at sea. A college chum posed as that missing mariner, filling my room with flowers and telegrams. My parents, troupers both, visited and pretended to be happy new grandparents. And then we drove to a country crossroads where I handed my blue-blanketed bundle to a kind social worker named Liz who took him away, to his unknown future. And I went on to mine, eventually finishing college, working, marrying, raising the kids society said I could keep.

There's no way I can account for the deep confidence that kept me from agonizing over the infant I'd named Michael, wanting him to have an archangel's protection. I simply knew in my bones that he was alive and well, a good man living a good life. Somewhere. I knew. Not in my head—my mind tweaked me often, challenging that serenity with unanswerable questions: What if he'd been given to terrible people? What if he'd caught an awful disease or been in an accident? Standing in front of the Vietnam Wall, the question was, What if he was drafted near the end of the war and his name is here?

I had no way of being sure, either way—I didn't know his name.

On a weekday afternoon in the mid-1980s I was home from work with the flu, watching television interviews with adoptees who spoke of their deep need to know their roots. The Oprah Show put up a card for a registry in New York that was connecting people who had lost each other. Michael might be like the adoptees I was seeing, needing to know more of who he was; I sent for the forms. If he too registered, I would be able to tell him whatever he wanted to know.

When no man born in Portsmouth, Virginia on July 17, 1954 registered with the service, I took it to mean that Michael, like me, had no empty space that needed filling. His life was full and happy, as was mine. Or—said the nagging voice—he just never knew about that registry.

In the late 90s, when the Internet made all things possible, I started asking questions on an email list of people seeking lost relatives in Virginia. There were angels on that list, knowledgeable people willing to coach others on the laws, to find state and agency records, to dispense encouragement. From my home on Whidbey Island, north of Seattle, I had friendly eyes and hands back in Virginia.

The chink in the wall built to separate family members was medical histories. As more and more diseases turn out to have genetic origins, it's only right that adoptive parents know as much as possible about their child's medical inheritance. Michael might need to know what predispositions to illness he could be carrying, and passing on. When my brother and both our parents were diagnosed with macular degeneration, I knew I should warn Michael.

My family doctor wrote up a summary of our medical history and sent it to the address my Virginia cyber-friends provided. The law, they told me, ensured that the information would have to be passed to Michael's mom and dad. Never mind that Michael was too old to still be living at home, the rules were that the information went to his parents—they might never have told him that he'd been adopted.

A soft-spoken social worker named Mary was soon on my phone. Was I free to talk? The circumspection of yesteryear—and rightly so. My husband had always known about Michael but Mary had surely made many a call into households where secrecy mattered.

She had opened a file on my "case," had forwarded the medical history to Michael's dad, and received a gracious letter asking her to thank me for being so considerate. He'd passed his son the information.

Michael was alive. It was a fine moment. And there was more. Without revealing any "identifying information," Mary told me that my son was a professional, married, and had two daughters.

It was more than I had ever expected to know. I had confirmation that he was alive and doing well; my assumption had been accurate. No more nagging questions. But I didn't stop—he might have questions, might be laboring under the weight of them, like the people in those stories of loss and reunion.

I sent the social worker a letter and photos to put in the file, all to be given to Michael should he ever ask to know more. Here are your grandparents, your brothers, a sister, your nieces and nephews—and the one in the straw hat is me, Ann Medlock, the woman who gave birth to you when she was a girl, the woman who can tell you whatever you would like to know about your beginnings.

"Men are much less likely to make contact than women are," Mary warned. "They worry about seeming disloyal to the mothers who raised them." But Michael's mom had died, which Mary thought might make it easier for him to reach out than for men whose moms were still living and possibly disapproving. Adoptive parents had been promised secrecy and a deal was a deal. I could understand any reluctance to change the terms of the agreement.

And indeed Michael sent assurances, via Mary, that he was in good health and thanked me for my concern, but made no overture toward knowing more.

A full two years later, his younger daughter developed a condition that my family had long dealt with. He asked Mary to find out more about his medical heritage.

After many cautious phone conversations with each of us, Mary told me that if we ever did meet, we were going to like each other "and that's not always the case, believe me." But still he had not agreed to contact, and had not asked to see the file where the names and faces of his kin were waiting.

My two sons and the daughter I'd adopted now knew about Michael, but it seemed that they were unlikely to ever meet him. This man was firm on his feet, his life was working. He was the son of people who had raised him well. I left it there, delighted with everything that I had come to know.

Four years after the first mediated, anonymous contacts, on May 6, 2004, I was in South Carolina, where my mother had been diagnosed with metastasized kidney cancer. I was looking at x-rays of her right thigh bone, almost eaten through by the cancer. It was already in the bones of her chest, in her arms—it was everywhere, and moving fast. There was nothing to be done but wait for death and deal with her pain. I had to tell her and my father that she was going into hospice care.

It was my birthday. The worst one ever. But that afternoon a message reached me that Mary wanted me to call her right away. Michael had filed the required paperwork that would open his file and tell him who I was. She was sending documents for me to sign that would complete the process of making this breach of the old wall legal. It was a birthday I'm unlikely to ever forget.

On June 3 my mother died. And Mary called to give me Michael's name and address. He had read the file; he wanted to exchange letters.

There was no emotional room for processing this stunning news. My mother was dead. The sight of her exhausted, lifeless body filled every space in my being. I put a bowl of gardenias on the table beside her bed, lit beeswax candles, put oil from a vial of frankincense on her forehead, promised her spirit that my brother and I would be sure Dad was well cared for.

Much too soon, the funeral director was there, with his black body bag and his gurney. As his van pulled away, the hospice nurse put several rings in my palm. I stared at them, saying nothing. "It's best not to leave jewelry ..." she tried to explain why she'd removed them from her patient's hand, not knowing that my silence was about more than holding my mother's wedding and engagement rings—I was also holding the wedding band I had bought to look married when I was carrying Michael.

I don't know why my mother had put it on—she'd never said a word about it—but she had worn it since I'd given Michael to Liz, the kind social worker, right into this last day of her life. And I had learned, this day, that Michael's name was Peter Newbould. I put the ring back on my hand, all these decades later.

On a dial-up line in that grief-stricken house, everyone asleep but me, I Googled the name and saw that he was a lobbyist in Washington for a national association of psychologists, and president of a neighborhood civic association in Alexandria. At Google Images a face appeared in horizontal segments on the maddeningly slow connection. Curly dark hair, a high forehead—not familiar—then Medlock eyebrows, Medlock-shaped blue eyes, a Medlock nose, mouth and chin. I was looking at myself in male form.

Ten days later, completely absorbed in moving my father into an apartment, packing up the accumulations of their lives, and closing their house, I found a Priority Mail package from Alexandria that had been in my parents’ mailbox for several days. It held photos of Peter Newbould with a beautiful wife and daughters. His letter told me he’d worked on The Hill all of his career, for many years as chief of staff for a Congressman, one I’d long admired. He worked at the Democratic National Convention every four years. He read constantly, loved to write, and to give speeches. He cared deeply about the health of democracy and about helping people with mental illnesses get the care they needed.

This was more than a physical family resemblance. I’d worked in Washington for a Senator and for the Democratic National Committee. I’d worked the national convention. I live inundated in books. I’m a writer. I give speeches on social activism. I started a nonprofit to foster more civic involvement by citizens. My friends are almost all social activists and psychotherapists—the ones who aren’t writers.

He included an email address and I responded to his letter online. His reply was immediate and the exchanges were rapid, years of missing information volleying back and forth between our computer screens.

There was constant delight as the revelations unfolded—the largest one for me: his adoptive father was a submarine captain, career Navy. I’d asked Liz to place him with a Navy family because I wanted him to have the adventurous upbringing that I had had, moving from base to base, always learning new things. Liz had said absolutely not—the Navy was too small a world and we would be too likely to come upon each other. And she had done it anyway.

I was laughing-out-loud delighted and I tracked her down to tell her so. She’d risen to run the agency, had now retired, but she remembered us—me, my parents, Michael, and the Newboulds, a Navy couple in their thirties who had adopted another boy from her agency a few years before she gave them Michael.

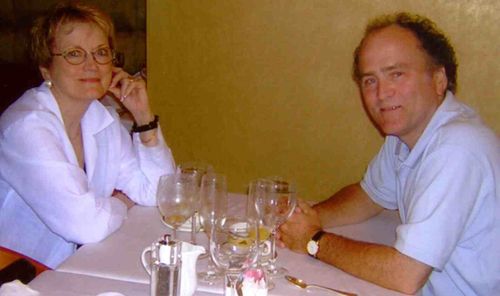

In July, I flew to Washington to meet him, arriving at my Dupont Circle room to find yellow roses on the mantel, brought there by “a charming man wearing a Kerry for President button.” The next day, I walked into the Willard Hotel in Washington for our lunch meeting. He’d arrived enough ahead of time to choose the perfect quiet table, was waiting, watching the entrance, after alerting the maitre’d that I’d be coming. It was good advance, as is said in the world of campaigning.

We hadn’t heard each other’s voices since I’d said goodbye when he was a week old and he had gurgled something back. Now I could say, “Happy birthday.” He was 50 that day.

We talked for over four hours, both of us pleasant and tentative, taking in everything said and unsaid—it was far too much to absorb, a firehose of ideas, images and feelings coming at each of us.

He had a good voice, a quick mind, a droll sense of humor, an easy confidence, an analog watch—the trivial and the serious were completely entangled. He wanted to know if his brothers were balding, as he was. No, they weren’t. And were they tall? Well, average. Would I have a mimosa? It was Mollie Newbould’s favorite, Mollie who was gone, who had raised this man so beautifully. We toasted his mom with champagne and orange juice.