This story was supposed to be published in MS, but the editors wanted to delete the ending and I refused, the ending being the point of the piece—a young man is guiding a boy away from fantasies of violence, and both are setting out into a world where violence is an ever-present danger. It was published intact by NAJ, the New Age Journal....

One of our favorite rituals is the one where I go into Phil’s bedroom on weekday mornings and open the blinds and he covers his head and mutters about cruel and inhuman mothers and I fuss about good-for-nothing teenagers until he’s on his feet. Sometimes David, who is five, helps out by sitting on his big brother’s stomach. It’s Saturday and David is sleeping in but Phil’s got a ball game scheduled in the park, so I start our usual routine.

My good spirits die instantly when the sunlight falls on a face I don’t recognize. The fine, strong bones have been replaced by purple quilting, and a jagged maroon line, bristling with suture knots, is gashed from his temple to his nose, barely missing the crease where his eye is now buried. There’s wadded, bloodied bandaging on the pillow.

How badly is he hurt? How did this happen? Why didn’t he wake me when he came in? The questions roar through my mind, distracting me from the fact that I’ve stopped breathing. I touch his shoulder hesitantly. He rolls over and I see the real Phil, still there in the other side of his face.

“Phil, hon, wake up now.”

He sits up, too quickly, and falls back, looking startled. His hand goes up to the wound.

“Oh shit,” he groans.

“Muhammad Ali or a Mack truck?” I ask, aspiring to our usual morning mood, knowing this is no time to crumble.

“Muggers. I got mugged.” The swelling affects his mouth and he’s finding it difficult to make his lips and jaw work.

I busy myself with finding the ice bag, banging cubes out of a tray and smashing them to fit the bag’s opening. It’s too late to stop the swelling, but I have to do something and ice will at least numb the pain. I notice the racket I’m making, realize I’m using enough energy on these helpless ice cubes to break bones—muggers’ bones.

My son’s distorted face is an alien presence, unwelcome and obscene. It is an enormous relief to erase it with the ice bag, to see only the son I know as he struggles with the story.

“I came around a corner on Eighth Street and there were these guys beating and kicking somebody on the sidewalk. It looked like they were going to kill him. He was barely moving. I started yelling and trying to pull them off and they just switched over to me. Two of them slammed me into a tree and another one came at me with a tire iron. Then a cop was shaking me and asking me if I was alright.”

I go to the medicine chest for fresh bandages and for time to steady myself. Grown men. Lots of them. With tire irons. A quarter of an inch to the left and I would be waiting in a hospital corridor to find out if his eye could be saved. A downward blow instead of a lateral and I’d be cabling Thailand to tell his father he was dead.

But he is here, in his own bed, alive and wincing as he touches his tenderized skin. I try not to count the stitches.

“That’s not all, Mom. After they grabbed the guys and threw them in the meat wagon, they got me and the one on the sidewalk into an ambulance, and the cop who was with us told me I was a maniac. “What are you, kid, some kind of nut? You went up against four guys.” He’s doing a perfect tough-cop imitation and laughs at himself. It isn’t a good idea and the laugh turns into a moan.

“The emergency room took my address and all. They’re going to send a bill.”

Something in his voice changes, there’s an edge to it, a challenge. “The cop was right, you know. I wasn’t any help at all.”

“Did the man they were beating die?”

“No. Somebody dialed 911 before I even got there. I didn’t make any difference at all.”

“What if that last swing, the one that got your face, had broken his skull? He’d be dead. You made a difference.”

“I couldn’t help him and I couldn’t help myself. I don’t know how, and it’s your fault!”

The cords are standing out in his neck, a palpable wave of anger is coming off him, and it’s all aimed at me. The real bill for this injury is being presented to me now, not in next week’s mail.

“Hey, kiddo. I didn’t belt you. I haven’t even spanked you since you got taller than me.” I’m speaking lightly, hoping to head him off, to prevent the weight of what is coming from landing on me. But there’s no stopping him.

“No! It was you and your non-violent crap. You haven’t raised me to survive out there. I don’t know how to handle myself, and you did this to me.”

He is fighting back furious tears, his voice filled with panic. For me, all the years of putting my principles into his head are coming together in this wounded face, in this anguished voice, in the awful sense that he may be right.

This is the child who would have been born in the middle of a bloody Congolese riot had there not been an unexpected transfer to Washington. Before he was two, he toddled into my Saigon bedroom singing, “Boom boom, maman!” as a rebel mortar emplacement in front of our house opened a barrage on the president’s troops. We pretended it was a game to live under a makeshift fort of mattresses, the shutters closed against stray bullets. I told him the explosions were firecrackers and read him fairy tales and held him a lot to keep us both from crying.

The day after Jack Kennedy was buried, this child of mine stood in line at Arlington with three daisies and a yellow rose and was awed when the military guards afforded him full honors, escorting him smartly through the picket fence, and laying his offering at the head of the raw grave.

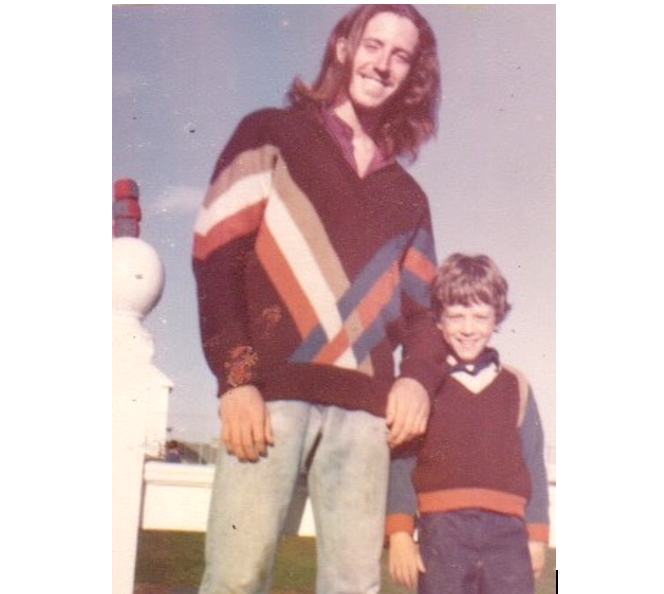

He marched early, carrying a picket sign in front of the White House before he could read. He was adorable. His picture made the wire services and his whole adult world showered approval on him.

While Bobby Kennedy’s funeral train rolled down to Washington, we sat on the floor and disarmed ourselves. I took apart the police revolver that had been in the bedroom closet, he broke up the plastic bazooka his father had sent him for Christmas, the only toy weapon that had ever been in our home.

He seemed to understand when we wore our dove buttons and linked arms and sang about giving peace a chance. But did he? He was a child, aping the grownups I brought into his world. And always I was there, blocking every move towards broad swords, model Messerschmitts, even squirt guns. No child of mine would think that pretending to cause pain was a good game.

When his school offered judo lessons, I vetoed his joining the class, in spite of the emphasis on defense. Such knowledge in a child’s mind and body might not, I suspected, be reserved for defensive crises.

Thieves, I explained, would want only things from him, and there was no thing he should consider worth injury to himself—or to the thief. When “three big guys” linked arms across the sidewalk behind the Museum of Natural History, he gave up his birthday bicycle—on his birthday. His first watch went to attackers in the park, but he managed to keep his favorite windbreaker when he guessed correctly that he could outrun the fellow who wanted it.

With each loss he was aggrieved and angry, and I talked to him about King and Gandhi and Thoreau and the brave Quakers I had known in Viet Nam. The Hindus had a word for what I wanted to teach him: ahimsa—“do no intentional injury.” It was not an easy philosophy for an American city boy to live by, but I required this of him.

It was clear that I would also expect him to be a conscientious objector when it came time to face the draft. He would not go off to kill Vietnamese boys he had played with. But we peaceniks had won; the war was over, the draft almost forgotten. Tran, Hung, and Dan had died in the jungles while their friend Philippe practiced jump shots and learned calculus.

Now Phil has met his own small war on a Village street corner and years of anger and frustration are bursting forth at me, telling me I’ve been a fool for trying to raise gentle males in a world that devours the gentle. Looking at his battered face, hearing the fury roaring out of this ever soft-spoken young man, I must face the possibility that I’ve raised him to be destroyed by a hostile world.

I want out. I want his long absent father to be here, to have been here all along, and I want him to say to him, “You handle this. I’m a woman. I don’t know how to father. I’ve blown it and I’ve injured our son terribly. Help him. Help me.”

David, my next victim, comes groggily into the kitchen in his rumpled pajamas and I pick him up and cuddle him into full wakefulness. This I know how to do. He looks at Phil and starts to cry.

“Don’t be scared, Dave. It’s just me. Not a monster.”

David goes cautiously to stand beside Phil’s chair and stretches up to soothe the hurt, but Phil holds his hand and tries to distract him.

“What do you want for breakfast, sport?”

“Not now,” says David and, putting his arms around his brother’s chest, he pats his back and makes there-there noises.

“Mom,” David says, looking at me with total confidence, “fix this.” He points to his brother’s face.

I burrow about in the refrigerator, not wanting them to see me cry or to know that I can’t fix anything, that I have no magic, no power to protect them, to make their hurts go away.

There is a great racket at the door and Phil’s friend Luke has arrived, swinging two softball bats dangerously near plants, mirrors, and people.

“Step it up, man. We got people to meet, people to beat. I figure we can take these guys by ten runs.” He stops when he actually looks at Phil and is, for what seems the first time in the years we’ve known him, quiet. Phil delivers a quick, unemotional accounting and Luke begins to shout even louder than usual.

“Man, you’re an idiot! You could be dead. For what? Some creep you don’t even know gets creamed—what do you care? You see something like that going down, what do you do? You walk on by, man. You walk on by.”

Luke gets the message that this is not a good day for Phil to take to the playing fields, and I manage to maneuver him out the door without anything in the apartment getting broken—another first for Luke. We can hear him pounding on the elevator door and yelling that he hasn’t got all day.

We sit over the remains of breakfast, the silence marked only by David’s crunching on his almond granola. Phil and I look at each other and dissolve into laughter.

“Testosteronitis, right? The guy’s got an acute case, maybe critical.” Phil’s diagnosis is a peace offering, a replay of the times I’ve talked to him about the differences between manliness and machismo, between true strength and bluster.

I am silently blessing Luke for providing the perfect absurd extreme, just when we needed to find our balance. Devastating as it is to see Phil hurt, it would have been more devastating to have produced a Luke. I repent my cave-in and reach out to my son.

“I want you to know I’m proud of you, of who you are and what you did. I mean, I wish you’d done something wiser like going for help or throwing rocks from a block away, but damn it, I’m proud of you. If you’d lived in Kew Gardens, Kitty Genovese would be alive. You’re a good man, and I love you and I’m not sorry for what I’ve taught you. Not at all. I think I’ll even be a little proud of me for being the mother of a man who didn’t ‘walk on by.’ My God you look awful.”

The barrier is down. We can hug and cry, and he can say that he loves me, that I’ve been right—almost.

The “almost” occupies us for hours—amazing hours in which my son instructs me in matters I have never wanted to consider. With patience, love and fervor, he urges me to address my attitude toward the persistence of evil.

“It’s not always enough to put out good vibes, Mom. I’ve watched you turn ogres into kitty cats, and sometimes I can do it too, but the magic doesn’t always work. There are still guys out there with tire irons in their fists and murder in their hearts and, I’m telling you, they don’t give a shit about anybody’s vibes.”

He cites chapter and verse, pulling down from the shelves books I’ve brought home, hoping he’d read. He has. He finds the passages in which don Juan tells Castaneda that he must live as a warrior, because the world is full of peril. We talk about the Bhagavad Gita and Krishna’s explanations to the reluctant Arjuna of just why he must fight the assembled warlords. We talk about Obi Wan Kenobee taking deadly action against galactic villains.

“The Force helps those who help themselves, Mom.”

He wins. We will check with friends to find a good judo school. He will finally be on his way to knowing he can stop Bad Guys, because he’s a Good Guy and he’s going to keep doing that. I can’t say I’m happy, but I am convinced.

The sound of gunfire overwhelms our voices. Bored by all this talk, David has been puttering in his room, working jigsaw puzzles, talking to himself, looking at picture books, and assembling his costume for the day. He’s sitting now in front of the television, which he’s rolled out of the hall closet where I hide it, wearing three shirts, his best pants, last year’s ragged sneakers, and a football helmet. He is totally, gleefully engrossed in watching a gangster shootout, in which he is participating by making a machine gun out of his right arm.

Phil turns the set off. David starts to howl.

“Don’t watch that crap, kid,” Phil says sternly. “Come on. I’ll take you for a walk.”

###