- Your name. The one that ties you to your people.

- I have one. I see it there, in the hundreds of records

- my son has put into a growing tree,

- looking for his place in it all.

- If you are Black in these united states, your family name,

- one that may have been assigned or borrowed,

- goes back only so far, then disappears, in a sea of evil.

- You will not find your place in it all.

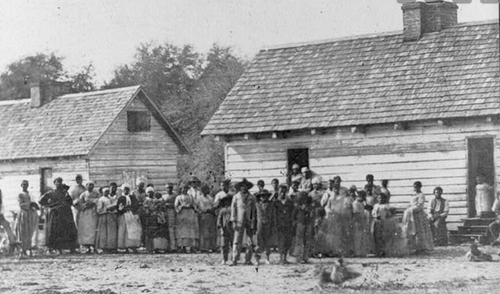

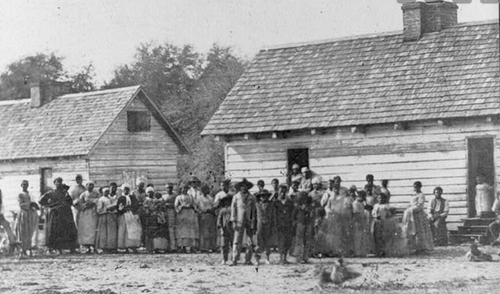

- Your family may be in one of the documents

- my son has unearthed in his searching.

- There is no way of knowing.

- Lavenia, negro woman

- Archy, negro man

- Alley, negro girl

- Luke, negro man

- Peggy, negro woman

- Cesar, negro boy

- Bought from Joshua Bland, April 22, 1774, for $364

- Sold to William Norris, December 1, 1818, for $147

- Bought from Frances Posey, February 2, 1834, for $580

- Year after year, sales and purchases,

- in column after column,

- in carefully inked ledgers.

- Such beautiful penmanship.

- Such meticulous record-keeping.

- Boys fetch high prices, as much as $791—

- such investments yield high returns

- in decades of crops planted, harvested, taken to market,

- in houses built, roads cleared, new properties sired.

- The names of the people bought and sold change,

- pages of people, “Christian” names only.

- To their buyers and sellers, “nigras” didn’t have families.

- But the family names of those “Christian” men are there.

- Again and again—my family name.

- .

- What is there to do, now?

- My Carolina father was a linthead,

- the bottom of the white pecking order in that harsh south,

- into the mills at 13, a runaway to sea at 16.

- There’s nothing to deed over, no blood-money to transfer.

- Generations of buying and selling human beings

- came down to one scared white boy running for his life,

- away from bosses who saw him as trash,

- away from a life of outhouses, and a death of white lung,

- away from a lesser, minor servitude to a boss’s demand

- for a return on the investment made in his meagre wages.

- And now it’s down to me

- staring at that ledger and wondering

- how the books can ever be balanced.

- There’s respect,

- for all whose humanity was denied,

- all who survived,

- all who were denied families, denied family names,

- all who died without their families around them.

- There’s attention,

- to the value and the needs of the living,

- with a voice,

- with a vote,

- with my own writing,

- with raising anti-racist sons,

- with welcoming a new, wider centering of power,

- with amplifying the voices of the long silenced,

- with years of putting their work before my own.

- It isn’t enough.

- I know.

- There is no enough.